"With the Greatest Admiration:" Lessons Learned from Correspondence Among Foundational Leaders in Public Health

One Health Newsletter: Volume 17, Issue 2

Introduction

n the late nineteenth century, medicine was adapting due to the wider implementation of the scientific method, establishing a metaphorical "Bronze Age" of disease understanding. Today, historical documents offer scholars the opportunity to draw modern lessons from key moments in history. Induction, distinct from deduction, is defined as "beginning with the observation and measurement of phenomena and then developing ideas and general theories about the universe of interest" (Bowling & Ebrahim, 2005). In this article, the authors detail primary archival materials from this era, and then inductively integrate conclusions about leadership during the nascent formation of One Health networks.

Foundational Ideas and Leaders in Public Health

One leader from the United States was John Shaw Billings (1838–1913), director of the National Board of Health (NBH) (1879–1882) and, preeminently, the founder of the National Library of Medicine (NLM). Billings corresponded with hundreds of physicians, veterinarians, and scientists in developing his collections (Garrison & Hasse, 1915). Another American physician leader, U.S. Army Surgeon General George Miller Sternberg (1838–1915) studied infectious diseases like yellow fever by searching for a bacillus carrier, although the virus wasn't isolated until 1930 (Kober, 1915; Prinzi, 2021).

Across the Atlantic Ocean, Robert Koch (1843–1910) discovered pathogenic bacteria with his postulates, including zoonotic agents of anthrax and tuberculosis (Goetz, 2014; Koolmees, 2000). European figures such as Birkenhead physician Peter Braidwood (1842–1905) and Francis Vacher (1843–1914) were critical in translating scientific discoveries into practice. Birkenhead was a key port where livestock and meat products were routinely imported and inspected. Vacher, Birkenhead Medical Officer of Health, distinguished animal diseases that posed zoonotic threats from those benign for humans (Vacher, 1881a; Vacher, 1881b; Vacher, 1882).

Non-physician figures were also important for the sanitation movement. Rudolph Hering (1847–1923), a civil engineer, was commissioned by the NBH to investigate European municipal waste treatment in 1880–1881 (Fuller, 1924). Studying dry removal and water carriage, he reported that moving waste by water to a treatment facility before public re-entry was advisable for developing U.S. cities like Manhattan, NY (Fuller, 1924).

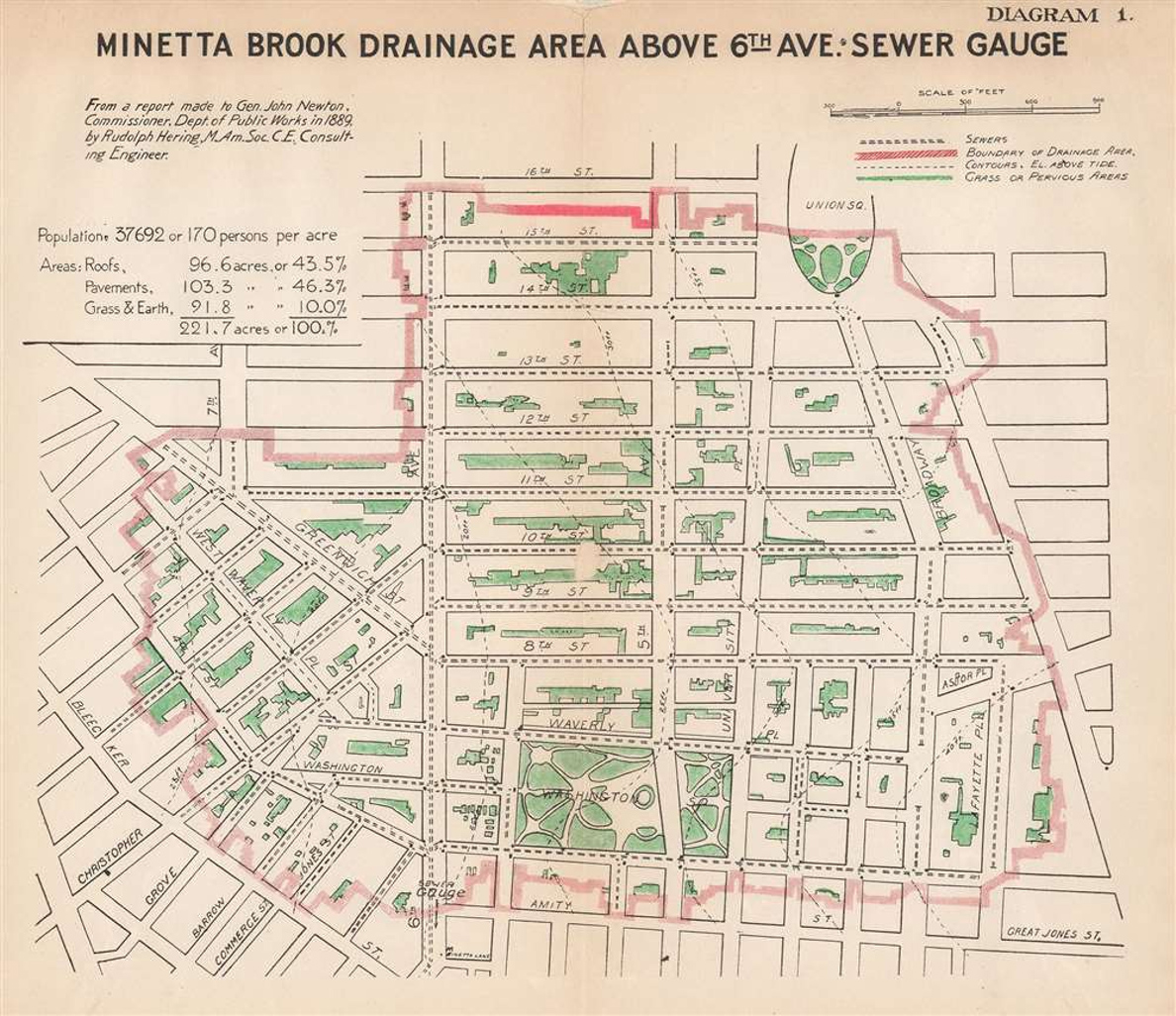

Figure 1: Map of drainage area in Manhattan, NY by Rudolph Hering, 1889. This is an example of work that Hering would have been producing at the time he was mentioned in Koch's letter to Billings (Hering, 1889).

Meanwhile, Koch studied tuberculosis, publishing three major papers in 1880 and becoming director of the new Institute of Hygiene at the University of Berlin in 1885 (Goetz, 2014). In 1882, Sternberg introduced Koch's tubercle bacillus to colleagues in the U.S. (Kober, 1915). Deeply interested in yellow fever, Sternberg "twice returned to Havana during the months of yellow fever prevalence, and visited Rio de Janeiro and Vera Cruz, also the town of Decatur, Alabama, during the epidemic of 1888" (Kober, 1915, p. 1234). Following these investigations, Sternberg published a report revealing that all claims of identifying the yellow fever cause had failed, including those of Brazilian Domingos Freire, who claimed "Cryptococcus xanthogenicus" (a fictional bacterium) caused yellow fever using a flawed method (Kober, 1915). These leaders' work inspired multidisciplinary studies of sanitation internationally, revolutionizing public infrastructure (Goetz, 2014).

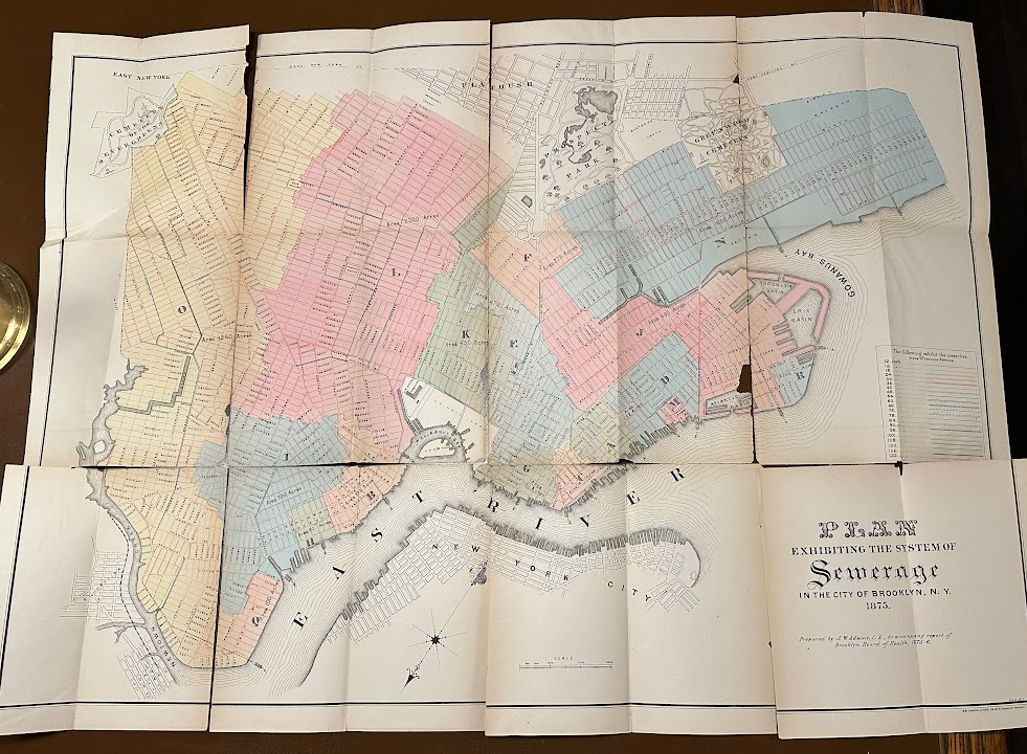

Figure 2: Schematic of sewer infrastructure in Brooklyn, 1876. This sewage map prepared for the Brooklyn Board of Health report, illustrates well the need for engineering-minded expertise, like that of Rudolph Hering, in public health (Adams, 1875).

Archival Materials: From One Bacteriologist to Another

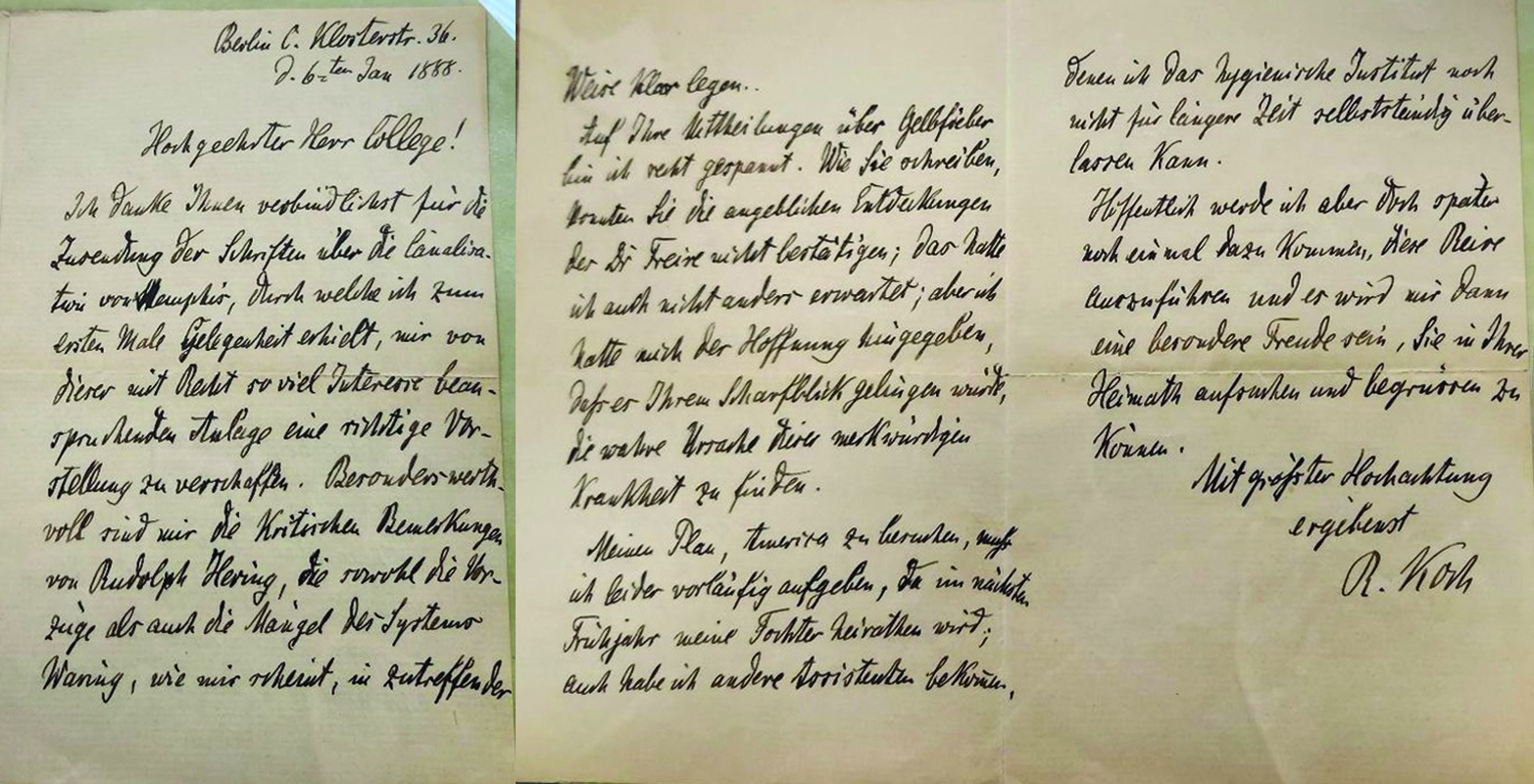

Figure 3: Letter from Robert Koch to George Miller Sternberg, 1888. Written on January 6th, 1888, from a Berlin address, Robert Koch writes to George Miller Sternberg in German discussing various public health matters (Koch, 1888).

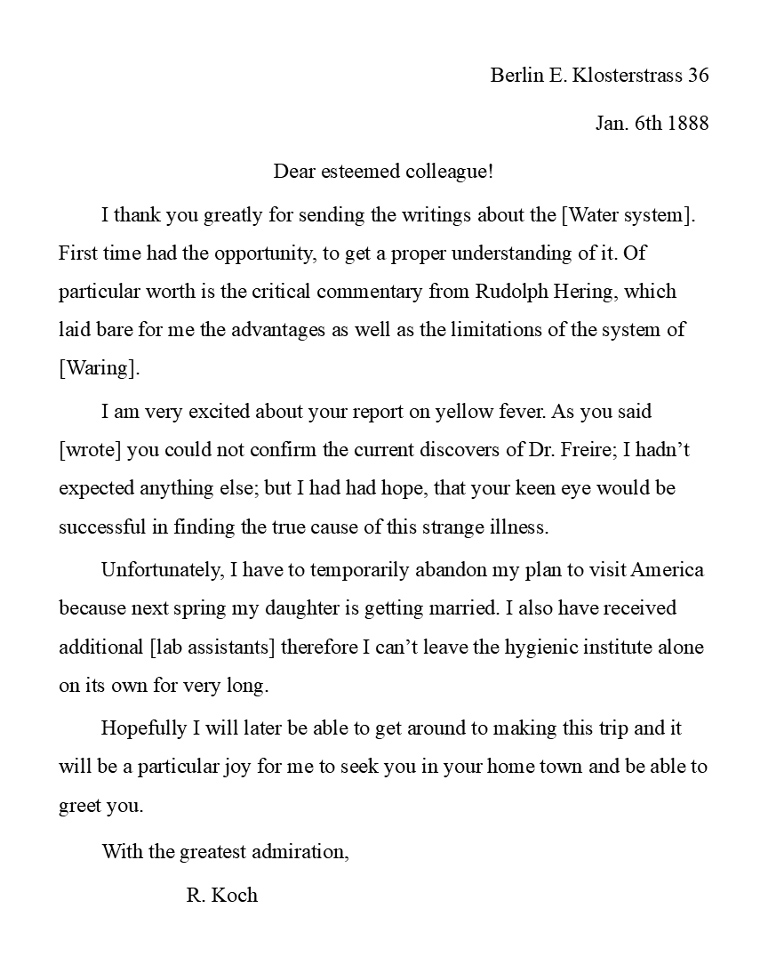

Figure 4: Letter from Robert Koch to George Sternberg, rough English translation. Since the original letter was written in German, a translation was prepared in consultation with Dr. Sara Luly, a professor of German at Kansas State University (Koch, 1888).

Writing from Berlin, Koch penned a letter (Figure 3) to Sternberg on January 6th, 1888. With context, much can be inferred about the relationship between Koch and Sternberg from this translation. Writing on January 6th, 1888, Koch would have been the director of the Berlin Institute of Hygiene. Koch's salutation of "Dear esteemed colleague!" suggests that he held Sternberg, the American bacteriologist, in high regard.

In paragraph one of Figure 4, Koch describes a publication sent by Sternberg, likely related to sanitary water systems (due to the word "Canal"), highlighting their interests in waterborne diseases, a critical focus of linking the environment to public health and the beginning of "One Health" ideas. Koch praises Hering, likely referencing the American sanitation engineer. The "system of [Waring]" possibly refers to Colonel George E. Waring Jr., member of the NBH that surveyed the Memphis yellow fever epidemic of 1879 with Billings (Garrison, 1915).

In paragraph two of Figure 4, Koch commends Sternberg's recent yellow fever publications, inferred to be commentary on Dr. Freire’s refuted studies in Brazil. Therefore, Koch trusted Sternberg's critical interpretation of Freire's incomplete study.

In paragraph three of Figure 4, Koch explains that he cannot visit Sternberg in America as he had planned, indicating that their correspondence is beyond strictly scientific communication. Koch desired proximity to his daughter before her wedding, adding a dimension of personality to the microbiologist, impossible to ascertain by merely reading his publications.

Koch concludes with hopefulness: "It will be a particular joy for me to seek you in your hometown and be able to greet you," further illuminating his friendship with Sternberg. The closing, "With the greatest admiration," served as an inspiration for this paper's title. This affectionate closing is not simply an antiquated customary practice; it is demonstrative of a true friendship, a genuine person behind the lab coat.

A Letter "Triangle"

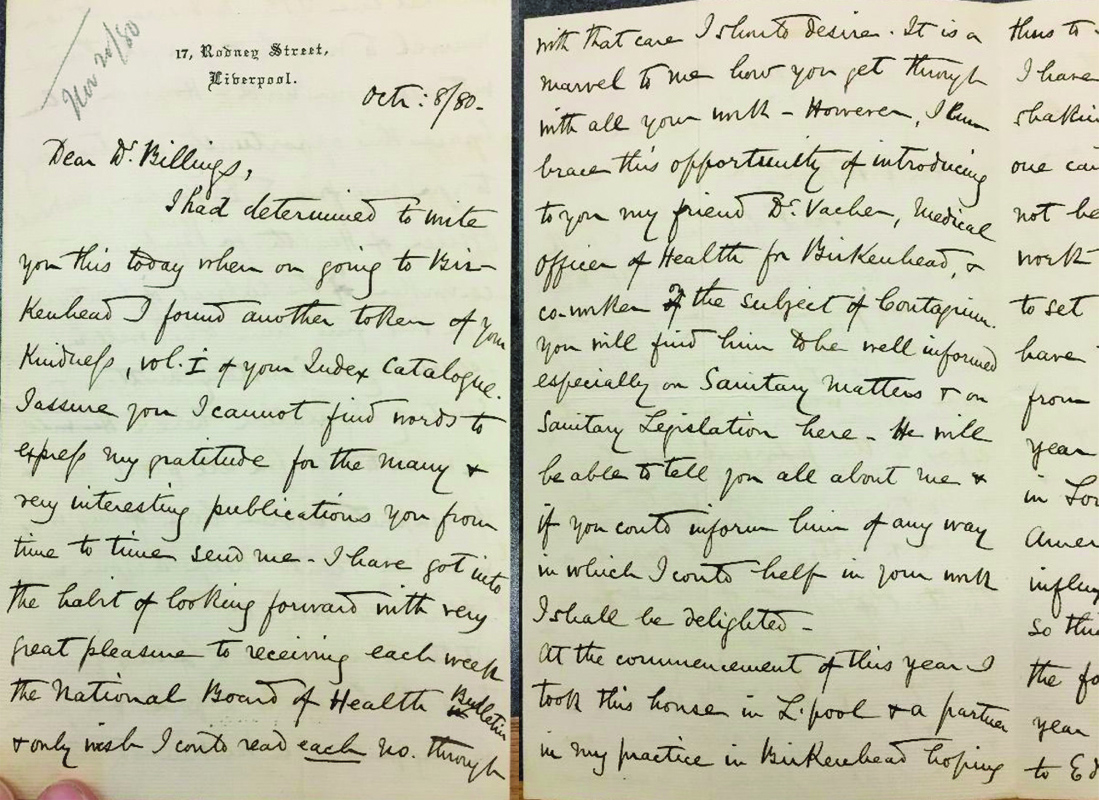

Figure 5: Letter from Peter Braidwood to John Shaw Billings, 8 October 1880. Braidwood wrote to Billings to introduce him to a valuable connection, his colleague Francis Vacher (Braidwood, 1880).

In late 1880, Braidwood wrote to Billings, introducing his colleague Vacher as "well informed, especially on sanitary matters," offering Vacher's expertise (see Figure 5, paragraph one). At this moment, Billings was director of the NBH, and Vacher was authoring his report, "What diseases are communicable to man from diseased animals used as food?" (Haynes & Kastner, 2019).

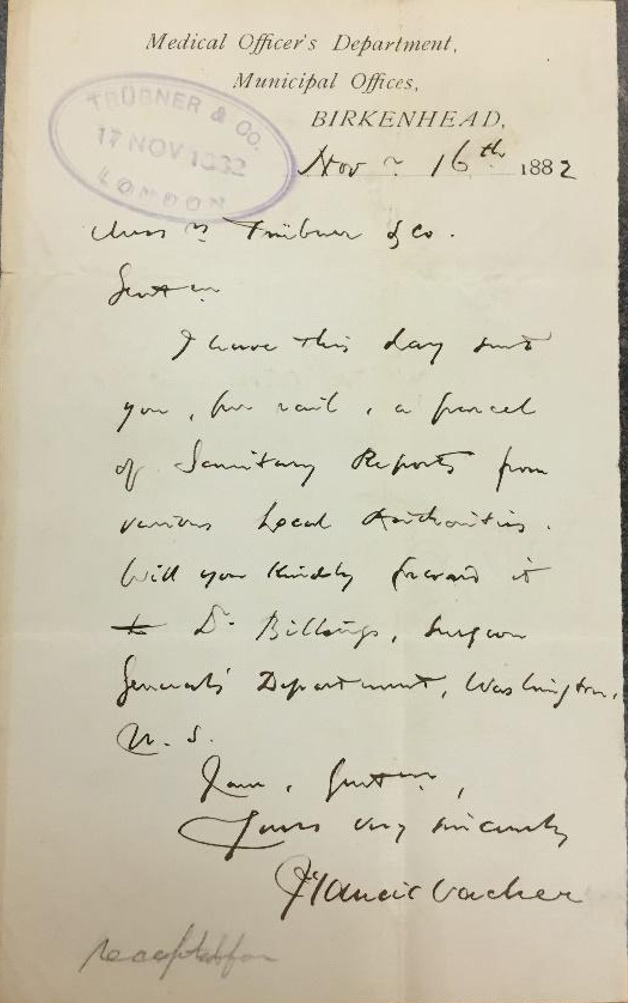

Figure 6: Letter from Francis Vacher to Peter Braidwood, 16 November 1882. This brief note from Vacher to Billings demonstrates Billings's use of Braidwood's connection to his colleague Vacher (Vacher, 1882a).

Two years later, Vacher penned a short message addressed to Billings: "I have this day sent you, by mail, a parcel of Sanitary Reports from various local authorities. Will you kindly forward it to D. Billings" (Figure 6). Vacher's contribution of valuable information to Billings exemplifies how international collaboration drives practical solutions to One Health challenges. Second-degree connections help grow relationship branches that develop into professional networks. Billings documented this phenomenon in his inception of the NLM (Garrison, 1915).

Inducing Lessons Learned from the Primary Sources

Collaboration of engineers, scientists, physicians, and medical officers reveals early One Health in action, and archival research illustrates these efforts. Koch’s infatuation with curing tuberculosis and Sternberg’s dedication to understanding yellow fever likely arose from inspiration to cure loved ones, although cures were just out of reach: tuberculosis was incurable before 1943 (Goetz, 2014). However, they laid foundations on which functional cures and treatments were later based.

Science is a historical tradition. Publications and correspondence are how the greater scientific community builds knowledge; Billings understood this as he collected papers to establish the NLM. Koch, Sternberg, and Hering published stacks of papers to communicate their discoveries and failures. These early public health leaders diligently devoted their lives to reducing infectious diseases, paving the way for advancements to be made in One Health. While one may never see the true fruits of their labor, they still meaningfully contribute to the causes they so desperately believe in.

Disclosure of Related Report. This is an excerpt from Schieferecke's University Honors Program Project, Kansas State University (Schieferecke & Kastner, 2025).

References

Adams, J. (1875). Plan exhibiting the system of sewerage in the city of Brooklyn, N.Y. [Map]. Center For Brooklyn History.

Bowling, A., & Ebrahim, S. (2005). Handbook of health research methods: Investigation, measurement, and analysis. McGraw-Hill Education.

Braidwood, P. (October 8, 1880). [Correspondence between Peter Braidwood and John Shaw Billings]. John Shaw Billings Papers, (MS C 81, Box 14). National Library of Medicine.

Fuller, G. W. (1924). Rudolph Hering: Died May 30, 1923. Journal (American Water Works Association), 11(1), 304–306. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41226833

Garrison, F. H. & Hasse, A. R. (1915). John Shaw Billings: A memoir. G.P. Putnam's Sons.

Goetz, T. (2014). The Remedy: Robert Koch, Arthur Conan Doyle, and the quest to cure tuberculosis. Gotham Books.

Haynes, J. & Kastner, J. (2019). Physicians welcome a veterinarian to problem-solve on tuberculosis: One Health meeting in Edinburgh, Scotland, in 1888. One Health Newsletter, 11(1). https://olathe.k-state.edu/research/one-health-newsletter/issues/vol11-iss1/edinburgh.html

Hering, R. (1889). 1889 Hering map of the Greenwich Village, New York City. Geographicus Rare Antique Maps. (2025). Retrieved September 17, 2025, from https://www.geographicus.com/P/AntiqueMap/minettabrookdrainage-hering-1889

Kober G. M. (1915). George Miller Sternberg, M. D., LL. D: An appreciation. American Journal of Public Health, 5(12), 1233–1237. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.5.12.1233

Koch, R. (January 6, 1888). [Correspondence between Robert Koch to George Miller Sternberg]. John Shaw Billings Papers, (MS C 81, Box 26). National Library of Medicine.

Koolmees, P. (2000). Veterinary inspection and food hygiene in the twentieth century. In D. F. Smith & J. Phillips (Eds.) Food, science, policy, and regulation in the twentieth century (pp. 53-68). Routledge.

Prinzi, A. (2021). History of yellow fever in the U.S. American Society of Microbiology. Retrieved April 3, 2025, from https://asm.org/articles/2021/may/history-of-yellow-fever-in-the-u-s

Schieferecke, G. & Kastner, J. (2025). “With the greatest admiration:” Lessons learned from correspondence among foundational leaders in public health. University Honors Program Student Theses and Projects. https://hdl.handle.net/2097/45322

Vacher, F. (1881a). Milk inspection and the control of the milk supply. North-Western Association of Medical Officers of Health, and E. Griffith and Son, Caxton Works.

Vacher, F. (1881b). What diseases are communicable to man from diseased animals used as food? T. Richards.

Vacher, F. (November 16, 1882a). [Correspondence between Francis Vacher and John Shaw Billings]. John Shaw Billings Papers, (MS C 81, Box 16). National Library of Medicine.

Vacher, F. (1882b). The accommodation for discharging, lairing, slaughtering and storing at the foreign animals' wharfs. North-Western Association of Medical Officers of Health, Birkenhead.

More Articles in this Issue