One Health Newsletter

Food Security and the Soil Microbiome

Authors

Marian Flaxman

Introduction

Food security is a growing issue that increasingly threatens human life. It is framed through a variety of lenses in the public discourse, principally focusing on key factors such as poverty, conflict, supply chain disruptions, and the impacts of global warming. According to the United Nations’ Committee on World Food Security, food security is a state in which all people, at all times, have physical, social, and economic access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food that meets their food preferences and dietary needs for an active and healthy life.1 At present, even the food systems within the wealthiest nations do not produce these outcomes, and in lower income countries the situation is even more dire. According to a recent report by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), a healthy diet is currently out of reach for more than 3.1 billion people worldwide.1

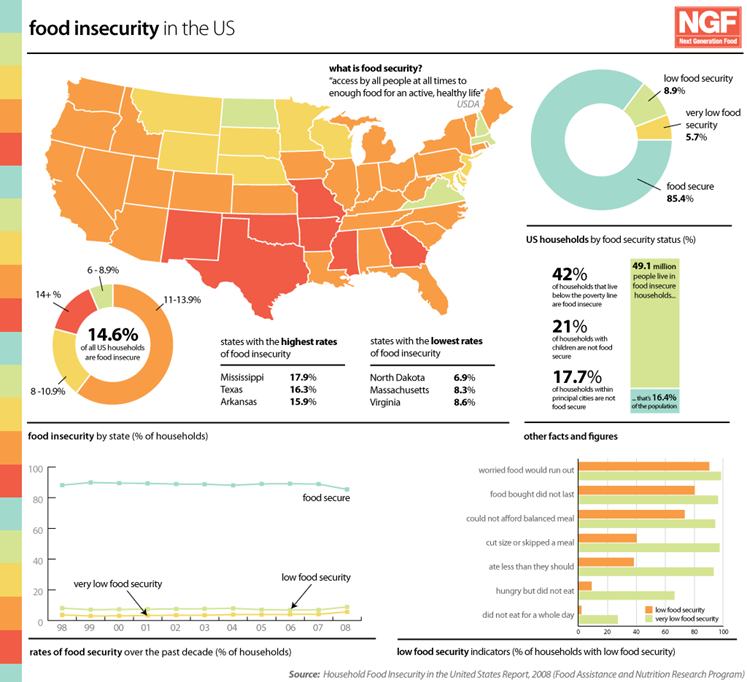

Figure 1: Food Insecurity in the United StatesSource: Household Food Insecurity in the United States Report, 2008

One fundamental threat to food security is the degradation of the soil microbiome. While supply chain issues challenge the way that food moves from producer to consumer, the disruption of the soil microbiome threatens our ability to cultivate food. This is inherently a global One Health issue, requiring that we consider the complex interactions between soil health, human and animal health, environmental health, and ultimately, food and nutrition security. It is necessary that policymakers shift their focus to regenerative land management practices which nurture the living microorganisms in soil. Only when we appreciate the importance of the soil microbiome and its central role in the One Health framework, will we move towards a sustainable system of agriculture that can provide food security to future generations.

Literature Review

In the two-hundred-and-sixty-page report, The State of Food Security in the World, 2022, the word “soil” only appears four times, mostly in the context of mentioning that current food security policies do not take soil health into account. In 2022, the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Technology held a meeting to discuss “cross-sector partnerships for food security and sustainability”. During the proceedings of the workshop, participants discussed current threats to food security, noting that gains made in agriculture over the last sixty years have come with important tradeoffs, such as “biodiversity loss, chemical runoff, water scarcity, [and] soil degradation”.2 They also explicitly reference the important connection between soil, agriculture, and the microbiome, calling for “a holistic approach” and stating that “the interaction among crops, soil, and the microbiome is complex [but should be kept] front and center”.2

However, these mentions are brief and could be easily overlooked within the context of the broader conversation.

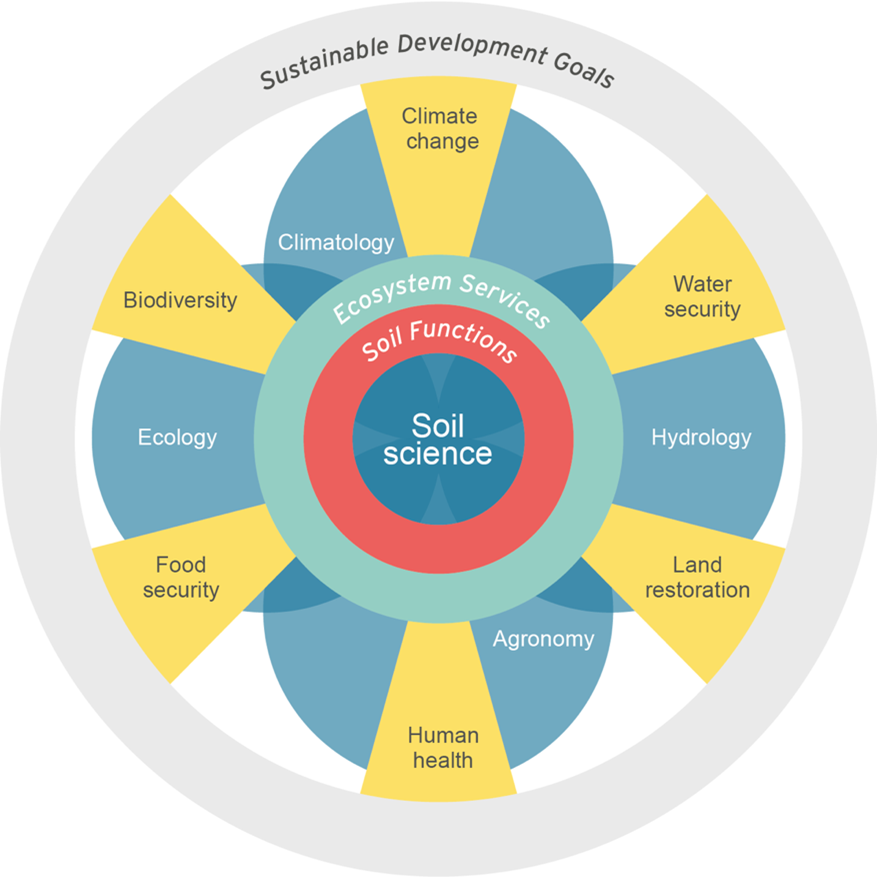

Figure 2: Soil Health is a Central Component of a Sustainable Future

Source: European Geosciences Union, 2016

Still, the evidence base supporting the critical connection between the soil microbiome and human health is building. These complex and overlapping issues were uniquely addressed in a review paper published in The European Journal of Soil Science entitled Soil, Food Security, and Human Health: A Review. In this paper, the authors examine the important role that soil plays in human health and society.3 They point to more than one hundred sources, illustrating the complex and intricate ways in which soil health and human health overlap.

In discussing soil’s role in food security, the authors write, “…soil and land are finite resources; they provide most of our food … filter water and supply essential minerals…while the population has almost tripled over the last 50 years, the world’s cultivated land area has increased by only 12%.3 They add that “…the quantity and nutritional quality of food underpins human health, and in turn, most food production depends on the soil…” .3 The threats to our soil are vast, and they note some especially pervasive ones, such as adverse environmental impacts from synthetic fertilizers, and soil degradation and erosion. The review illustrates the critical connection between soil health and human health and offer a framework to assess these connections, but they do not provide a path forward.3 For that, we must turn to sources that illustrate the ways in which soil ecology, and the soil microbiome, are the functional underpinning of healthy soil, and thus protect food security.

Bakkar et al. (2020) discuss the history of plant and soil microbiome knowledge and imagines a future in which society harnesses traditional knowledge, coupled with modern technology and understanding, to preserve soil health and sustain agricultural production.4 The authors describe Western knowledge of soil microbiomes going back to 1904, when German scientist Lorentz Hiltner stated, “I am convinced that soil bacteriology will…directly affect and determine agricultural practice”.4 They also describe a knowledge boom that occurred around 2012, when researchers began to sequence plant microbiomes, and our functional understanding of the role of microbiomes in plant health began to grow. This research has illustrated plants’ abilities to select for certain microbes, due to their unique microbial functions which may alleviate plant stress by selectively adjusting the chemical composition of the soil surrounding their roots. This understanding of soil microbiology and plant health emphasizes the need to maintain robust microbial colonies in soil. Unfortunately, many common farming practices (i.e, synthetic pesticides or fertilizers), disrupt and degrade the soil microbiome, leaving plants increasingly vulnerable to disease.

One of the most widely discussed threats to food security is fungal pathogens,5 but the conversation rarely addresses the role a robust soil microbiome can play in controlling the overgrowth of fungal threats. Instead, much of the focus remains on the development of genetically modified plants that aim to resist these pathogens and new classes of antifungal drugs. Unlike some pathogens which may be disrupted by changing climates, fungi are highly adaptable to temperature shifts. This creates a compounding threat to food security, as our agricultural production is challenged by fungal threats and global warming, while simultaneously needing to scale production to feed a rapidly growing global population.

Discussion

The threats to global food security are complex, and they require a wide-reaching, holistic solution. The health of the soil microbiome should be the focus of all policy initiatives addressing global food security. A robust, diverse soil microbiome provides protection against fungal pathogens by establishing healthy competition, conditioning the soil for optimal plant health, and driving nutrients into plants, reducing the need for additional nitrogen inputs. Due to widespread soil degradation, plans to restore soil should include the application of probiotic, beneficial microbial inputs to promote soil health and sustainability. Approximately 52% of the land used for agriculture around the world is moderately or severely degraded due to erosion, salinization, or contamination, and 75 billion tons of fertile soil are yearly lost due to erosion.6 To address these losses, microbes that promote the health of the soil microbiome provide a solution, as they play a vital role in ecosystems, help to sequester carbon, assist in nutrient cycling, and increase soil productivity and crop yields.6 Soil microbes can remediate degraded soil, pose no known threat to the environment, and improve the immune system of plants, making them more resistant to pathogens, thus decreasing the need for pesticide application.7 Already, there are companies in the agriculture market who sell unique consortia of microbes designed to increase soil health and resiliency. One such company, GivLyfe, notes that the microbes in their product “were carefully chosen for their ability to fix nitrogen and carbon from the air, make important nutrients like phosphorous and potassium more available to plants, improve the structure of the soil, and make it better able to hold water”.8

Microbiomes are complex, and there is likely not one single colony that will benefit all regions, terrains, and plants, but rather a wide variety of diverse cultures that will need to work together to perform the essential functions of a healthy, global soil microbiome. This complexity cannot dissuade our desire to harness beneficial microbes for soil health, plant health, and food security. Studies of microbes have shown great promise, especially when looking at protecting plants from pathogens and improving root architecture and nutrient uptake while also suppressing soil-borne pathogens.4 We must aim to learn from nature and store the soil microbial communities that are currently alive and well, so we can learn from them, and turn to them in the future for use in the restoration of degraded soil.9

Conclusion

Depleted soil, devoid of beneficial microbes, is fertile ground for pathogens that can harm both plant and human health. Understanding the ways in which the soil microbiome aids in agricultural security is essential to human survival and global food security. Although food security policy often centers on topics such as subsidies, climate change, and global conflict, threats to our soil underlie and overrun all these other factors. The microbial sterilization of soil represents an extreme threat to food security.

The soil microbiome can be nurtured towards improved agricultural yields and plant resiliency, while potentially assisting in the fight against climate change. While it is important to study fungal pathogens and consider the role of politics and society in food security, we cannot overlook the importance of understanding soil as a living habitat. As we look to the future and assess the rapidly increasing agricultural demands worldwide, we must ensure that microbes and the essential role that they play in soil health and food security remain at the center of the conversation.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to my advisors, Dr. Tomoko Steen and Dr. Jean Paul Gonzalez for their continued guidance and support. Thank you to my professor Dr. Richard Calderone for his work on fungal pathogens, and for inspiring my interest in the overlap of the soil microbiome and food security.

References

-

World Health Organization. The state of food security and nutrition in the world 2022. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/the-state-of-food-security-and-nutrition-in-the-world-2022. Accessed March 5, 2023

-

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Policy and Global Affairs; Government-University-Industry Research Roundtable, & Whitacre, P. (Eds.). (2022).Supporting Cross-Sector Partnerships for Food Security and Sustainability: Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief. National Academies Press (US).

-

Oliver MA, Gregory PJ. Soil, food security and human health: a review. European Journal of Soil Science. 2015;66(2):257-276. doi:1111/ejss.12216

-

Bakker PAHM, Berendsen RL, Van Pelt JA.The Soil-Borne Identity and Microbiome-Assisted Agriculture: Looking Back to the Future. Mol Plant. 2020;13(10):1394-1401. doi:10.1016/j.molp.2020.09.017

-

Kettles GJ, Luna E. Food security in 2044: How do we control the fungal threat? Fungal Biology. 2019;123(8):558-564. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.funbio.2019.04.006

-

Díaz-Rodríguez A, Salcedo Gastelum LA, Félix Pablos CM, Parra-Cota FI, Santoyo G, Puente ML, Bhattacharya D, Mukherjee J, Santos-Villalobos SDL. The Current and Future Role of Microbial Culture Collections in Food Security Worldwide. Frontiers in Sustainable Food. 2021;4. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2020.614739

-

SP Kumar T, Yadav M, Gill SS, Chauhan NS. Plant-microbe interactions for the sustainable agriculture and food security. Plant Gene. 2021;28. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plgene.2021.100325

-

GIVLYFE Growing the future. About us - givlyfe - growing the future. GivLyfe. (2022).https://givlyfe.com/about-us/ Accessed April 7, 2023

-

Annapurna B, Dubey S, Sharma S. Storage of soil microbiome for application in sustainable agriculture: prospects and challenges | SpringerLink. Environmental Science and Pollution Research International. 2022;29(3). doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-17164-4

Next story: Strategies to Reduce Food Insecurity Associated with Global Antifungal Use

Contact Us