Giardia intestinalis in Argentina: A One Health Field Study

Introduction

Boundaries did not exist as we traversed tall, grassy fields and ducked under barbed wire fences, wincing when an occasional barb stabbed us through our snowman-like layers of clothing. As the sun began its morning ascent on a new winter day of June, we hurried into the dark forest to locate our first group of black-and-gold howler monkeys (Alouatta caraya). As our eyes adjusted to the dim light, we peered through the branches and finally spotted the cluster of howler monkeys snuggled together against the chill.

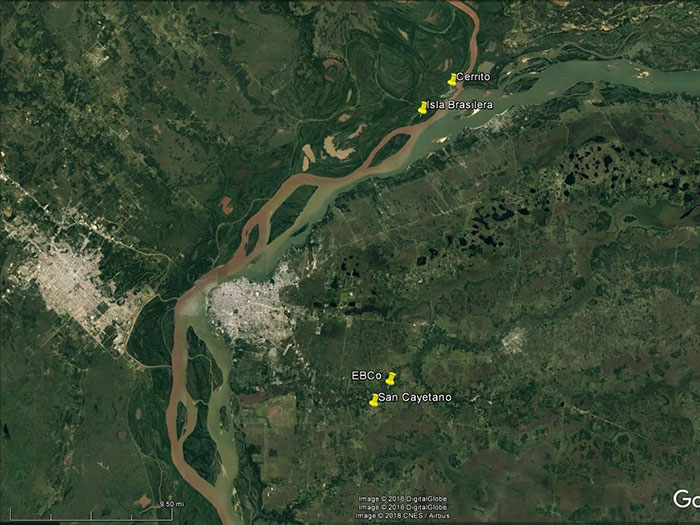

During the summers of 2016 and 2017, I conducted fieldwork in Corrientes, Argentina, as a part of a long-term collaborative study on howler monkey health and conservation (Figure 1). My project assessed the prevalence of Giardia intestinalis infection and genotypes in a diverse array of species, including black-and-gold howler monkeys, humans, dogs, and cattle, in Northern Argentina (Figure 2). My work incorporated interactions between wild howler monkeys and humans and domestic animals to gain a holistic perspective on the ecological and epidemiological drivers of giardiasis in the ecosystem. Here, human, animal, and environmental health are inextricably linked and reflective of the One Health model.

Figure 1. A lagoon in the middle of the fragmented forest at the Estación Biológica de Corrientes. (Photo credit: Sahana Kuthyar).

Figure 2. Satellite map of the study sites in San Cayetano (27°34’ S, 58°42’ W), the Estación Biológica de Corrientes (27°30’ S, 58°41’ W), Isla Brasilera (27°20’ S, 58°40’ W), and Cerrito (27°17’ S, 58°37’ W) in northern Argentina.

Giardiasis as an Exemplary Zoonotic Disease

G. intestinalis is a ubiquitous zoonotic parasite that can exhibit cross-species transmission in localized ecosystems. G. intestinalis infects four major groups of mammalian hosts: humans, wildlife, companion animals (dogs and cats), and livestock (Thompson 2014). Transmission of the parasite from host to host can be intra-species or zoonotic (inter-species) and can occur concurrently in a given area (Thompson 2014; Thompson 2000; Thompson and Ash 2016). Hosts can become infected directly through fecal-oral contact (inter- and intra- species transmission) or indirectly (environmental transmission) through ingestion of contaminated food or water (Thompson 2014; Ryan and Caccio 2013; Sprong et al. 2009).

The potential sources of exposure to zoonotic G. intestinalis are numerous, including sources of environmental contamination, amplified infection spread in wildlife, and cross-transmission from companion animals and livestock to humans (Thompson 2014; Thompson 2013). Increasing anthropogenic activity in Argentina is forcing wildlife species, including howler monkeys, to live in ecological overlap with humans and domestic animals. This ecological overlap among species at the human-wildlife interface presents the high potential for zoonotic disease transmission.

Black-and-gold howler monkeys are sentinels of ecosystem health as they can inform on potential disease circulation and outbreaks in a variety of species (Figure 3). They can survive in fragmented forests and cross terrestrially from forest patch-to-patch, allowing more contact with other species. In our work, we sampled howler monkeys as a wildlife proxy for zoonotic transmission of G. intestinalis, as they interact in varying degrees with humans, dogs, and livestock.

Figure 3. A group of female howler monkeys huddled in the trees at daybreak. (Photo credit: Sahana Kuthyar).

Into the Field I Go

I was a part of an interdisciplinary team of park rangers, a veterinarian, primatologists, and students, all under the guidance of Dr. Martin M. Kowalewski, the director at the local field station, Estación Biológica de Corrientes (Figure 4). We bonded over dodging howler monkey feces, chasing panicky cattle, and shivering through cold morning sunrises. Because this collaboration allowed for a robust sampling methodology and a dynamic flow of ideas from different perspectives, we were able to apply our research efforts to the larger context of One Health and biodiversity conservation.

Figure 4. Sahana Kuthyar at the entrance to the Estación Biológica de Corrientes, a protected natural area in Northern Argentina. (Photo credit: Angelina Godoy).

Through non-invasive sampling, we obtained samples indirectly from fecal deposits of different species. As a team, we avoided any physical contact with the animals in order to protect the health of all sampled species and to prevent any shifts in the potential zoonotic cycle. Non-invasive sampling is especially important when studying wildlife and when sampling a diverse array of species, as researchers could unknowingly introduce novel transmission pathways.

We collected fecal samples from free-ranging howler monkeys from 7:00AM to 11:00AM in semi-fragmented deciduous forests. Each howler monkey group, composed of three to 21 individuals, varied in their degree of interaction with humans and domestic animals. Remote groups were located on Isla Brasilera (27°20’ S, 58°40’ W) (Figure 2) and did not have any contact with humans and domestic animals. Rural groups were at the field station (27°30’ S, 58°41’ W) and surrounding the Parque Provincial San Cayetano, where they had high interaction with cattle. Village groups were located in the towns of San Cayetano (27°34’ S, 58°42’ W) and Cerrito (27°17’ S, 58°37’ W) and had high interactions with humans and dogs.

We planned to collect fecal samples from humans as well as from cattle and dogs associated with human households. Of course, fieldwork almost never goes perfectly! We found that not all humans wanted to participate in the project, and not all had both cattle and dogs. Nonetheless, each participating household was given an alphabetical letter, and each species (humans, cattle, and dogs) was labeled with that household letter and an individual number. Prior to data collection, all protocols were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at Emory University, in Atlanta, Georgia. Both oral and written consent were obtained in Spanish and were documented on IRB-approved study forms.

In fieldwork, cultural and social protocol is equally as important as scientific protocol. The townspeople have long-term knowledge of the land and an intrinsic appreciation for the howler monkeys. The community also cares about the health of their families and their animals and were enthusiastic to actively participate. We created a comprehensive behavior and symptom-driven survey to integrate their knowledge into our study.

Lasting Impressions and Lessons Learned

Household sampling required a sit-down conversation, which could last between 30 minutes to an hour, depending on how talkative the person was. As a foreigner, I needed to establish trust with the local people. During these conversations, speaking the local language was crucial. In my pilot session, I realized I would be facing a learning curve, as the Spanish spoken in the town (a mix of Spanish and Guarani) was not necessarily the Spanish I had learned in the United States. Both the vocabulary and accent were different, so I had to learn the intricacies of Correntina dialect (Guaranitico) Spanish.

Many people invited us into their homes to share mate (an herbal infusion of Ilex paraguariensis), a traditional drink taken hot or cold, and to chat about current local happenings. When I visited again in 2017, a massive flooding event had occurred and left a significant mark on the ecosystem. We spoke about their observations of altered howler monkey behavior, their struggles to manage infrastructural damages from the flood, and their problems with water potability in their homes. These people had the day-to-day knowledge I was craving, knowledge that did not exist without fieldwork. To them, these conversations might have been a normal part of daily life, but to me, they were an essential part in gaining a true understanding of the interconnectedness and resilience of this ecosystem.

Fieldwork provides an important hands-on opportunity to truly understand a system of interest. I observed a diverse landscape that was much richer than the one I had envisioned in my head. The numerous species’ interactions were much more complex than I had imagined. The kindhearted people I spoke with were much more naturally involved in the ecosystem than I had thought. By participating in fieldwork and collecting my own samples, I made real human connections. Even when I returned to my desk in the United States, I knew I was working with real animals and people – real characters in a story and not just random combinations of numbers and letters on an Excel spreadsheet. Using these memories as a base of knowledge and inspiration, I was able to construct a scientific narrative that shed light on unique transmission events and dynamics.

The value of empirical data, based on researcher observation and experience, has decreased in the general landscape of the scientific community. Nowadays, it often appears that results must be statistically significant to be “science”. However, the numbers never tell the full story. Social and anthropological sciences remain strongly attached to the fundamentals of observation-based qualitative research. Biological significance is equally as valuable. Fieldwork allows scientists to engage closely with their subject matter and discover detailed knowledge of their ecosystem. Moreover, in the One Health framework, fresh data from fieldwork is essential given that transmission dynamics can change rapidly due to the connectedness of the people, the animals, and their changing environment.

When I arrived in Corrientes on that fateful June evening in 2016, I took on the responsibility of telling this One Health story. Fieldwork, just like science, is neither straightforward nor easy, but it is extremely valuable. As I reflect on my field experiences, I remember trekking kilometers through the forest and plains, picking brambly burrs off my clothes, and wading across rivers with sodden socks. Yet, I also remember watching the sweet play of juvenile howler monkeys, making homemade pizza, and wandering along the senderos (forest paths) in hopes of glimpsing capybaras and caimans. Today, as a canal is being built, while the forest suffers and vanishes, further increasing ecological overlap, I can only hope that the One Health approach to solving these intricate health challenges will take effect fast enough to one day return it to a happy and healthy forest.

Bibliography

Ryan, U., Caccio, S.M. (2013). Zoonotic potential of Giardia. Int. J. Parasitol. 43, 943-956.

Sprong, H., Cacciò, S.M., van der Giessen, J.W. (2009). ZOOPNET network and partners. Identification of zoonotic genotypes of Giardia duodenalis. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 3, e588.

Thompson, R.C.A. (2000). Giardiasis as a re-emerging infectious disease and its zoonotic potential. Int. J. Parasitol. 30, 1259-1267.

Thompson, R.C.A. (2004). The zoonotic significance and molecular epidemiology of Giardia and giardiasis. Vet. Parasitol. 126, 15-35

Thompson, R.C.A. (2013). Parasite zoonoses and wildlife: one health, spillover and human activity. Int. J. Parasitol. 43, 1079-1088.

Thompson, R.C.A., Ash, A. (2016). Molecular epidemiology of Giardia and Cryptosporidium infections. Infect. Genet. Evol. 40, 315-323.

Author

Sahana Kuthyar, MS in Environmental Sciences

Lab Manager, Amato Lab, Department of Anthropology, Northwestern University

*Note: Fieldwork for this project was completed while the author was affiliated with Emory University.

Next story: Wildlife and One Health: From Jackal to Humans

Contact Us