Modernizing the Public Health System

The Need for Change

Throughout the past thirty years, there have been significant efforts to define and revitalize the United States’ public health system. The chronic underfunding and unstable budgets for public health departments, with funding given to specific programs on an annual basis, makes prioritization and strategic planning difficult (Institute of Medicine 2012). As a result, there is considerable inequity in the effectiveness, efficiency, and availability of public health services. Public health law is the application of legal powers and duties of the government as well as maintaining due limitations to those powers which may constrain autonomy, privacy, liberty, proprietary or other legally protected interests in order to assure the health and welfare of the public (Gostin & Wiley 2016).

The role of local health departments has evolved over time in response to pressing issues, though most public health law across the nation is rooted in antiquated legislation. In the early 20th century, governmental public health focused on the eradication of communicable diseases. Improved disease epidemiology, and response and improvements to sanitary conditions of the population – most of which were due to achievements of significant policy activity – led to a decrease in incidence of infectious disease. However, chronic diseases soon became more prominent public health threats, leading to a shifting focus for the public’s health in today’s world. The current legal infrastructure may not address contemporary challenges, such as chronic disease and injury prevention, as effectively as it facilitated approaches toward communicable diseases. Prioritization on addressing chronic disease risk factors, often related to lifestyles, has been a new challenge for public health, with regulations to prevent disease often met with strong political opposition. This is further complicated with modern influences such as global transportation that may spread diseases to new locations and increasing the likelihood of epidemics related to zoonotic pathogens. Antiquated laws may not supply sufficient authority to governing institutions to tackle these contemporary issues, confirming the need for modernization.

|

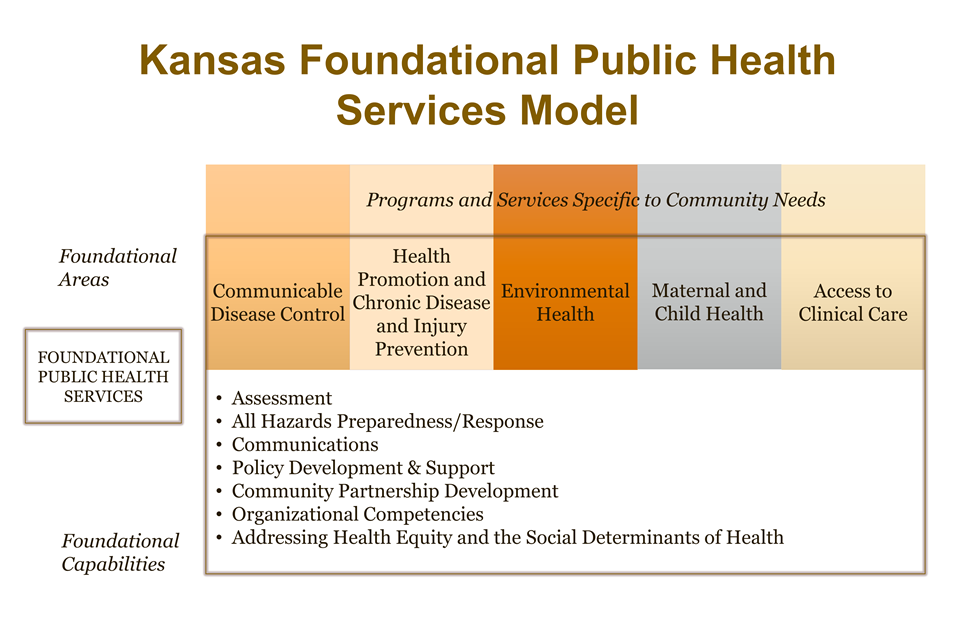

Figure 1. Kansas Foundational Public Health Services Model. (Source: Community Engagement Institute, Wichita State University, 2017). |

The Modernization of Public Health

The modernization of public health policies, practices, and standards has become an initiative by governances at every level. The term “modernize” is used to encompass the widespread updating of those laws, practices, and standards to address contemporary circumstances and challenges (Institute of Medicine 2011). Functions such as the management of immunization registries and syndromic surveillance systems or conducting multi-sector interventions to alter the built environment are not often well-organized within existing public health law. As such, some governances may not interpret a vested authority to provide modern activities. This makes sense, however, given that most public health laws have not been systematically updated for some time and many pre-date current knowledge of the factors which lead to disease. These issues convey the necessity for policymakers to routinely, systematically and comprehensively review public health policies to create clear authorities and standards for safeguarding the public’s health (Institute of Medicine 2011). Further, there needs to be sufficient capability and capacity across the public health system to effectively deliver these services.

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) – now the National Academy of Medicine (NAM) – has shepherded the nation in recent years towards the evolution of public health, focusing on the effects of decreased funding and difficulties in communicating the value of public health, ultimately leading toward identifying definitions for ‘public health’. An IOM committee introduced the concept of a “basic set or minimum package of public health services,” further defining a set of “foundational capabilities as an array of basic programs no health department can be without” (Institute of Medicine 2012). The IOM committee recommended this concept to improve upon the limitations of current paradigms, and it created momentum for a model to be universally available at the local level and typically provided by governmental public health. Services included within these models may be most proper when meeting the following decision characteristics (Washington State Department of Health 2017):

- Population-based preventive health services that target specific areas defined by geography, race, ethnicity, gender, illness or other health conditions (e.g., water fluoridation, creation of walkable communities);

- Governmental public health services in which the only or best potential provider of the service is a governmental entity (e.g., disease surveillance and epidemiology); and

- Mandated services provided by the public health authority (e.g., communicable disease reporting).

Over the years, most public health services models have been discrete sets of services that governances labeled as ‘essential’, ‘core’, ‘basic’, ‘foundational’, and other similar terms. Each of these models defines services that should be available to all citizens, often delivered by governmental public health. States across the nation have moved toward the adoption of such models, including Kansas.

A Kansas Context

Kansas governments, like in most other states, offer a broad array of services to support the public’s health. Some of these are required by state law or are contractually bound in return for state or federal funding. Other services vary by local priorities unique to each authority, addressing needs relevant to each community. Local health departments outside of urban areas tend to be more engaged in more individual or clinical services, as local priorities dictate. Many local health departments in Kansas struggle to provide the most basic public health services in their community, a symptom of having a fragmented public health policy framework. Each of the challenges described in the national context are similarly present within Kansas, the most significant challenges being limited funding (including the restrictions of local property tax lids), the role of politics, and expanding responsibilities.

There are presently many policy gaps in the Kansas public health system that hinder the ability of agents within the system to authorize or implement activities to build a strong public health system. At present, the primary legal infrastructure found in Kansas statutes is incapable of addressing most population health needs. Many public health statutes have stagnated – with some Kansas public health statutes left unreviewed for more than forty years. These challenges widened the gap between the current public health system—the structure, funding, and laws that support public health—and a strong public health system that will ensure basic protections critical to the health of all Kansans, no matter where they live.

In September 2015, the Kansas Association of Local Health Departments (KALHD) conducted a visioning event which resulted in the adoption of the following vision statement (Hartsig 2017):

“KALHD’s vision is a system of local health departments committed to helping all Kansans achieve optimal health by providing Foundational Public Health Services (FPHS).”

The vision statement provided guidance toward adopting a clear public health services model based around the minimum package concept: the Kansas Foundational Public Health Services Model (Figure 1). The model includes Foundational Capabilities –cross ‐cutting skills and capacities needed to support programs and activities – and Foundational Areas – substantive areas of expertise and program ‐specific activities best provided by government. Presence of these capabilities is key to protecting community health and achieving fair health outcomes for each of the programs that should be available in every community in Kansas. In some cases, the role of the public health agencies is to simply assure that people have reasonable access to certain services provided by a third party.

A recent review of Kansas statutes found loci of alignment and departure between the Kansas FPHS Model and legal authorities for public health (Orr 2018). Of interest for this article are two Foundational Areas − Communicable Disease Control and Environmental Health – that serve as examples of laws for further consideration and update.

The Communicable Disease Control area includes programs and activities to prevent and control the spread of communicable diseases. Authorities and requirements for disease reporting, investigation, and containment were clearly found, while the general administration of activities was implicitly authorized within law. Gaps persisted for specific activities such as partner notification services for newly diagnosed cases of sexually transmitted diseases (e.g., syphilis, gonorrhea, HIV) as well as for directly observed therapy for the treatment of individuals who have active tuberculosis. The Environmental Health area includes programs and activities to prevent and reduce exposure to environmental hazards (e.g., livestock or animal waste as public nuisances). Authorities and requirements for identification and abatement of hazards as well as licensure and permitting are well-defined and general administration of the program are implicitly authorized within law.

Primary barriers to delivering both services are rooted in the enactment of specific enabling laws as well as the enforcement of those laws. These issues are not specific to Kansas but are prevalent within governances of every level.

What Can Be Done

The present circumstances create a number of questions to be explored, ranging from the necessity and impact of having a more consistent governance model across public health systems to whether a conscious effort should be made to focus on fewer public health governances with greater capacity to deliver important services. Overall, there is an abundance of need for the public health sector to better connect to other parts of the public health and medical system. In reviewing current structures and exploring possibilities, governmental public health at all levels may evolve to deliver a better future for our ever-changing society.

References

- Gostin, L. & Wiley, L. (2016). Public health law: power, duty, restraint. 3rd ed. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Hartsig, S. (2017). Kansas foundational public health services model development. Topeka, KS: Kansas Health Institute. Available at: http://www.khi.org/policy/article/17-16.

- Institute of Medicine. (2011). For the public’s health: revitalizing law and policy to meet new challenges. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

- Institute of Medicine. (2012). For the public's health: investing in a healthier future. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

- Orr, J. (2018). Review of Kansas state laws applicable to the Kansas foundational public health services model. Unpublished manuscript.

- Washington State Department of Health. (2017). Public health modernization (FPHS) implementation, 2017-18. Presentation to subgroup in Summer 2017. Olympia, WA: Washington State Department of Health. Available at: PDF LINK.

Author

Jason M. Orr, MPH

Analyst, Kansas Health Institute

Former Emergency Preparedness Coordinator for the Riley County Health Department

Contact Us